Quick Fire: 5 Questions with MMFA Curator Erell Hubert

Erell Hubert, Curator of pre-Columbian Art at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, shares the archaeological tool that she can’t live without, and weighs in on how curators can combat the illegal trafficking of antiquities.

You’ve been doing archaeological fieldwork in Peru since 2008. Is there a favourite artifact that you’ve come across in the past nine years?

Many artifacts come to mind, from a fragment of Moche ceramic decorated with an anthropomorphic club to Tiwanaku obsidian points. My favourite artifact may however be a small figurine which I did not excavate myself, but rather discovered when analyzing material from the Moche site of El Castillo in the Santa Valley for my master’s thesis years ago. It was found below the latest floor of a residential compound and probably dates from about 700 to 850 CE. Even though it measures less than 5 cm, the burnishing of the surface and the painted details allude to the care taken in producing this object and, therefore, to the importance awarded to it. Its small size also suggests that it may have been used as a personal talisman by someone living at the site.

You and your colleague Victor Pimentel of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts have been involved in making the origins of objects in the Museum’s Ancient Americas collection more transparent in order to call attention to the question of cultural heritage. What is significant about this issue, especially for Latin American countries?

The vast majority of pre-Columbian objects now in museums across the world entered collections due to the looting of sites. Their original context is lost, and with it a lot of information about the people who might have produced and used them. Looting continues to be a grave problem for many Latin American countries with sites being destroyed in search of objects which may be valuable on the art market. While a change in museum practices will not put an end to the illegal trafficking of antiquities, it is our responsibility as curators to make sure we are not complicit in such trafficking by doing thorough provenance research. Making this information available to the public contributes to both furthering provenance research and raising awareness about the importance of preserving cultural heritage.

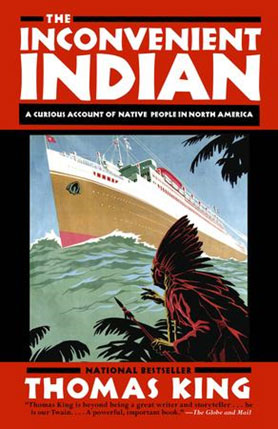

What are you reading right now?

Your lecture touches on the ways in which museums have represented “Moche culture”. What new discoveries associated with Moche art have changed the ways in which museums can represent it?

In recent years, the number of Moche sites scientifically excavated has increased dramatically and with it our understanding of the Moche. Excavations in new geographical areas within the region where Moche material culture has been found as well as excavations in more varied types of sites, including smaller rural sites, has revealed a more complex picture of the Moche than previously thought. Academic research cannot be directly translated in museum displays as it is a different medium. However, museums can work towards presenting a less monolithic image of “Moche culture” by addressing the variability of experiences associated with objects according to time, regions, status, and/or gender. In temporary exhibitions in particular, this can be achieved by making more use of scientifically excavated objects with known contexts.

What archaeological tool can you not live without?

I have to go with the most obvious tool, my trowel. Several tools are essential on fieldwork but there is a certain personal ownership associated with the trowel which differs from the other tools. My trowel was made by an artisan in San José de Moro in Peru. Some call his trowels “Morotown” as he is inspired by tools produced a by an American company well-known among archaeologists.

ERELL HUBERT will be at the Gardiner on Tuesday May 16 from 6:30 to 8 pm for a special talk entitled Looking Through the Glass: How Museums Constructed “Moche Culture”, part of the Gardiner Signature Lecture Series. $15 general admission, $10 Gardiner Friends.