Making Future Artifacts in Gentrifying Times

by Nataleah Hunter-Young

Below the glitz, glamour, and luxury of the newly renovated Yorkdale Mall lies the Yorkdale Community Arts Centre, where Art Starts brings professional artists and marginalized Torontonians together to collaborate. This summer, the Gardiner Museum joins forces with Art Starts and designers Calla Lee and Prateeksha Singh to run Reclaiming Artifacts, an arts project for the Museum’s Community Arts Space.

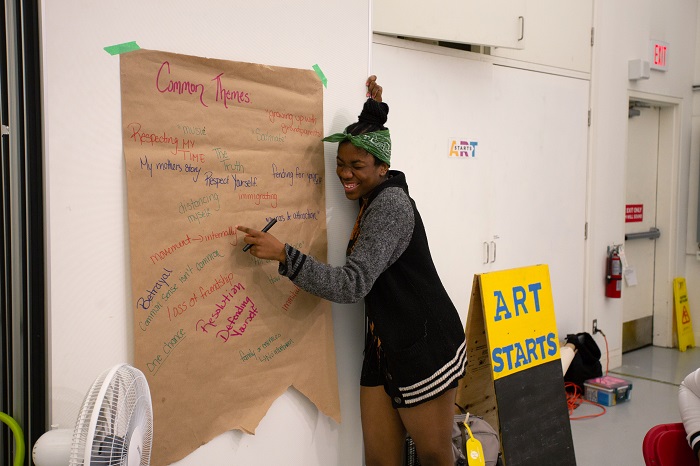

As part of the project, Lee and Singh invited a group of 15 to 18-year-olds living in the Lawrence Heights community to think about material culture in the past, present, and future. Meeting every Tuesday for six weeks, the group discussed what artifacts are, imagining what items from the past they might find if they drilled deep down into the earth. Or, in the same vein, wondering what items youth their age might be using in the year 2050—a process that will culminate in the creation of personal artifacts to be included in a fictional time capsule for future generations to find.

I visited the group on weeks two and five to observe the young visionaries at work. Each week’s program ran similarly, including: a “check-in,” where everyone shared how they were doing that day; a brainstorming-style activity, to help get the wheels turning; a making session; a meal; and a “check-out,” where, on my first visit, participants shared their self-care plans for the week—a wise list of pronouncements like drinking more water, going to class, being more social “because my friends are getting salty,” and “cutting off all my exes.”

Gathered around a timeline laid out across two six-foot tables, participants shuffled through VHS tapes, old video game consoles, magazine clippings, and other relics from times past, working together to figure out when, between 1960 and 2015, each item originated. While two of the youth discussed whether the boyband in the photo was NSYNC or the Backstreet Boys, others peeked at the copyright dates on the albums, or confidently placed the items they remembered seeing before.

“Oh! It’s the brick!” one of the participants shouted, picking up a picture of the first mobile phone. “That’s gotta go in the 1960s.”

“They didn’t even have phones then!” said another, correcting the person who’d put the iPhone 1 under 1965.

What may have existed five years before they were born might as well have been 50 years removed. And that’s the thing about material culture—moments pass quickly and we can lose sight of the impact that they have.

In many ways, this project has additional resonance with the young participants, as their community undergoes major changes to the social and built environment—what the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) is calling “revitalization,” but what many others across the city understand to be gentrification. The difference? Window dressing or semantics, depending on where you sit, but the objective is clear: to change Lawrence Heights from a low-income community into a much higher income community that is sure to become increasingly more inaccessible to preexisting residents. Phase 1 of the development will replace 233 low-income units while building over 800 new private market-rate units and is set to be completed in 2021.

“They’re taking us out of the area we grew up in and putting us somewhere else,” said one of the participants, when asked what she understood about the development.

“They’re breaking up families,” replied another. The despondency was shared among the group, but so was the sense that they would find a way through it.

“Is it because of the violence?” someone asked, when the facilitator inquired about why they thought it was happening.

“They want it to look rich instead of ghetto,” said another voice. “They want other people to live here.”

“You don’t have to watch your community change and not be a part of it,” the facilitator assured them. “We want you to think about how you’re going to be a part of the future.” And that set the tone moving forward.

When I joined them on week five, their personal artifacts were starting to take shape. “S” was moulding clay into a hyper-realistic detailed model of her hand, making the ASL sign for “I love you,” but what she was calling her “gang sign.”

“It represents friendship to me. Whenever I see my friends, I throw it up,” she said. “The nails are going to be pink.”

“K,” who was working hard on a beautiful rendering of her mother embracing her baby sister, told me that she has three siblings and that her mom has done everything to make sure that all her kids have it better than she did. A mother’s love, materialized.

Considering how much will change for these young people over the next few years, it strikes me that they want to be sure future worlds don’t forget compassion. Thirty years from now, what would you want the future to know?

–

Nataleah-Hunter Young is a PhD student in Communication and Culture at Ryerson University in Toronto whose general research interests include visual culture, Black visualities, documentary media, civic engagement (broadly defined), and video art. This blog post was commissioned in support of Reclaiming Artifacts, a Community Arts Space project led by design researchers Calla Lee and Prateeksha Singh in collaboration with youth artists from the Lawrence Heights neighbourhood and Art Starts. See the works made by the young artists at the Museum from August 2 – 16. Community Arts Space is generously supported by TD Bank Group.

Images: [Header Image] Calla Lee [1] Prateeksha Singh [2] Calla Lee [3] Calla Lee [4] Calla Lee [5] Kaitlin Kealey [6] Kaitlin Kealey]