Five groundbreaking women ceramic artists you need to know

Can you name five women artists? How about five women ceramic artists? In support of the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ third annual #5WomenArtists campaign, we’re highlighting five women ceramic artists in our collection whose groundbreaking works have changed the landscape of contemporary ceramics.

Shary Boyle

Shary Boyle discovered ceramics in a hobby class for grandmothers, reinventing their vintage figurine molds with her subversive use of obsolete decorative, slip-casting, and assembly techniques. Known for her feminist rethinking of traditional porcelain forms, Boyle uses the social contexts and myths associated with their histories to explore issues such as class and gender injustice, vulnerability, relationships, and sexuality: “In ceramics and in life I am so curious about non-dominant or marginalized knowledge, continually seeking surprising collaborations that bridge seemingly disparate worlds.” Notably, Boyle represented Canada at the 2013 Venice Biennale, and will revealing a new public sculpture on the Gardiner’s Front Plaza this year.

Magdalene Odundo

Magdalene Odundo originally intended to be a graphic designer, but fell in love with pottery after an introductory class during her studies at the Cambridge College of Art and Design. Best known for her hand-built ceramics and impressive use of the coiling technique, Odundo’s works are deeply rooted in traditional practices that she learned from master potters in Kenya and Nigeria, with influences from Pueblo potters’ blackware in the American Southwest. Odundo often fires her works repeatedly to achieve her distinctive silken surfaces and rich colour palette, creating sleek, amorphous forms that encapsulate the best of traditional and modern ceramics.

Ruth Duckworth

Ruth Duckworth had an incredibly diverse career history. Originally a stone mason, she started her own traveling puppet show after WWII broke out, and made a living carving tombstones before taking up ceramics in her 40s. Influenced by her background in sculpting, Duckworth turned away from wheel-throwing, instead creating hand-shaped works that were initially met with dismissal from leading potters at the time, including famed studio potter Bernard Leach. However, her innovative approach to clay quickly caught on and was key in the development of the Modernist style in sculpture. Throughout her career, Duckworth created everything from delicate clay vessels to monumental outdoor stone and metal sculptures, changing the way we think about clay and its many possibilities.

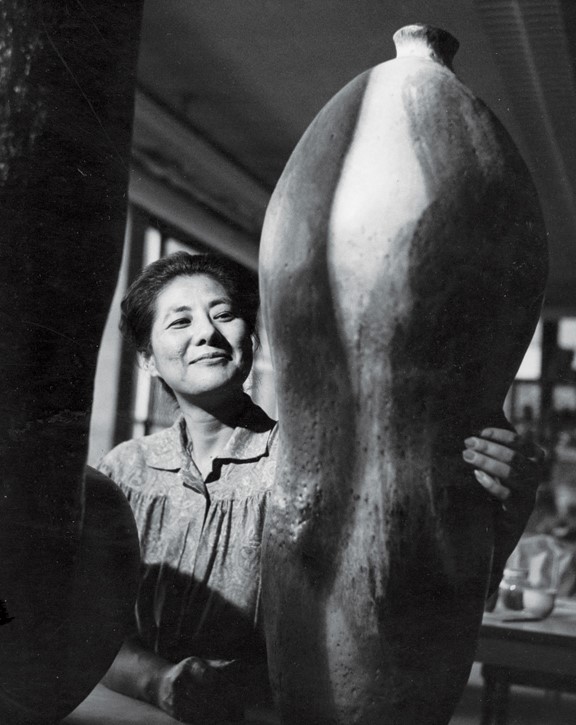

Toshiko Takaezu

Toshiko Takaezu was instrumental in the 1950s movement that elevated ceramics from craft to art. She embraced the potential of clay as a medium for sculpture rather than functional objects, using glazes in a way that evokes abstract expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock, while still possessing the calm, meditative qualities of traditional Japanese pottery. Takaezu is known for her closed forms, vessels that lack large enough openings for them to function as bowls or jars. Influenced by Zen Buddhism, she saw her ceramic practice as an outgrowth of nature, seamlessly interconnected with the rest of her life: “I see no difference between making pots, cooking, and growing vegetables.”

Ann Mortimer

Known as Canada’s “doyenne of clay,” Ann Mortimer was a key player in the development of ceramic art in Canada. Mortimer’s career spans more than half a century, during which she served as the President of The Canadian Guild of Potters, The Canadian Crafts Council, and the Ontario Crafts Council. She is renowned for her delicate, hyperrealistic porcelain umbrellas, which were inspired by her visits to China. Her work is held in the Gardiner’s permanent collection, and the Ann Mortimer Studio on the Museum’s lower level houses daily clay classes, workshops, and school groups.

[1] Shary Boyle. Photo courtesy Island Mountain Arts [2] Magdalene Odundo. Photo courtesy Atlanta Daily World [3] Ruth Duckworth. Photo courtesy LA Times [4] Toshiko Takaezu, Photo: John Paul Miller, ca. 1960s; Courtesy American Craft Council [5] Ann Mortimer. Photo courtesy Studio Ceramics Canada