Event Navigation

Connections: Canadian And British Studio Ceramics

The Gardiner Museum brings together people of all ages and backgrounds through the shared values of creativity, wonder, and community that clay and ceramic traditions inspire.

- This event has passed.

Connections: Canadian And British Studio Ceramics

May 31, 2012 - April 14, 2013

This exhibition of 30 works from the 1960s to the present highlights Canadian ceramists’ strong ties with the British studio pottery movement. Focusing on immigration, apprenticeship, and education, the exhibition investigates the ties that bind, underscoring the challenges of interpreting and transcending British traditions. The exhibition draws largely from the Gardiner’s Raphael Yu Collection.

Exhibition Programs & Events

Thursday June 7, 6:30 – 8 pm

Panel Discussion

Moderator: Rachel Gotlieb, Senior Curator

Canadian studio potters Thomas Aitken, Scott Barnim, Robin Hopper and Roger Kerslake discuss their ties to the British studio pottery movement.

$15 General; $10 Members

About the Artists

Thomas Aitken

“Many of my influences, both historical and contemporary came from the United Kingdom and Northern Europe. Coupled with the tempting diversity of clays available, it seemed an obvious place for me to go and study. I arrived at a time when the craft scene was energetically redefining itself with a new generation of competent makers like Edmund de Waal and Chris Keenan. Visiting studios and galleries and seeing a wide range of functional work and makers earning their living from clay confirmed for me that this was the path I wanted to follow.”

— Thomas Aitken, 2012

Scott Barnim

“My life-long connection with British ceramics began on the side of the road in southern Ontario, waiting for the bus, shuffling through the mail box for my Ceramics Monthly. In the spring of 1976 they ran a two issue feature on British ceramics. I was a kid in the final year of secondary school growing up in a family of rural craftsman. From this humble background the tradition of apprenticeship within British pottery was something I could understand and respect. Mick Casson and Alan Caiger-Smith are two icons of British ceramics that have had the most impact on my career. Mick encouraged my work with salt-glazed Stoneware in the 1980’s challenging me to engage completely in the traditions of saltglaze that I grew up around in the Brantford area. In the mid 1980’s it was Mick’s guidance that directed me to study in Cardiff for my Masters, and it was Alan’s personal support that helped me through the process. The influence of Alan was a longer process, the example of a potters life worth emulating, the constant curiosity, the joy of work shared in a studio setting, the importance of a work/life balance. How Mick and Alan went from an inspiring article in Ceramics Monthly to men whose guidance and friendship continue to shape my career remains a bit of a mystery to me. They opened the world of British ceramics to me in a very personal way, not only the work I make, but the way I work and the way the studio is organized is firmly rooted in the British tradition.”

— Scott Barnim, 2012

Kent Benson

“He [Cardew] was the most powerful person, I’ve been around. It was kick-wheels and thatched roofs. It was Africa.”

— Kent Benson cited from John Mahoney, Stanstead Journal 4, November, 1992

John Chalke

“My early self-teaching was through the Bernard Leach school of pottery in England—the Anglo-Japanese alliance of the 1920s and 1930s in which Leach brought in Zen philosophy and the awareness of the ‘unknown craftsman’. And he opened my eyes to wonderful things. So I went off to Japan, as well as to the Middle East and Korea, looking for other sources.” –

— John Chalke, cited from “Bridging East and West,” Artichoke 2002

Robin Hopper

“I feel very Canadian, even though I was born in England. My work is totally Canadian.”

— Robin Hopper, cited from John Flanders, and Hart Massey. The Craftsman’s Way: Canadian Expressions. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981

Tam Irving

“The Leach apprentices were important. They brought out the Leach message and through their own work they gave an example of what the Leach aesthetic was all about. Initially I didn’t understand what they were doing. They were not at all mechanical in feeling. Their pots were looser in contrast to the tight and hard-edged Scandinavian aesthetic that was more prevalent in Vancouver before they [the apprentices] returned. On reflection, I realized that the Leach apprentices had the advantage of understanding more clearly the expressive possibilities of thrown forms…This realization was slow to dawn, however, and it took a while for me to understand the Leach aesthetic.”

— Tam Irving, cited from Scott Watson, Naomi Sawada, and Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery., Thrown: British Columbia’s Apprentices of Bernard Leach and Their Contemporaries (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, 2009)

Roger Kerslake

“Timing and circumstance guided by early ventures in clay. Bernard Leach had been asked to build a small pottery [at Dartington Hall the famous art colony in South Devon] literally 150 years from my home. The seed was cast…My fascination with the clay medium became enriched that summer of 1952 when I stumbled upon a potter’s convention at Dartington Hall. There were was a Leach potter’s wheel set-up in the courtyard. The treadle was unreachable by one potter’s legs, so, by invitation I willingly pushed the treadle for him by hand at a constant pace. Unknown by me at the time, but learned a few years later, the diminutive potter was Shoji Hamada! Karma perhaps?”

— Roger Kerslake, 2012

Alexandra McCurdy

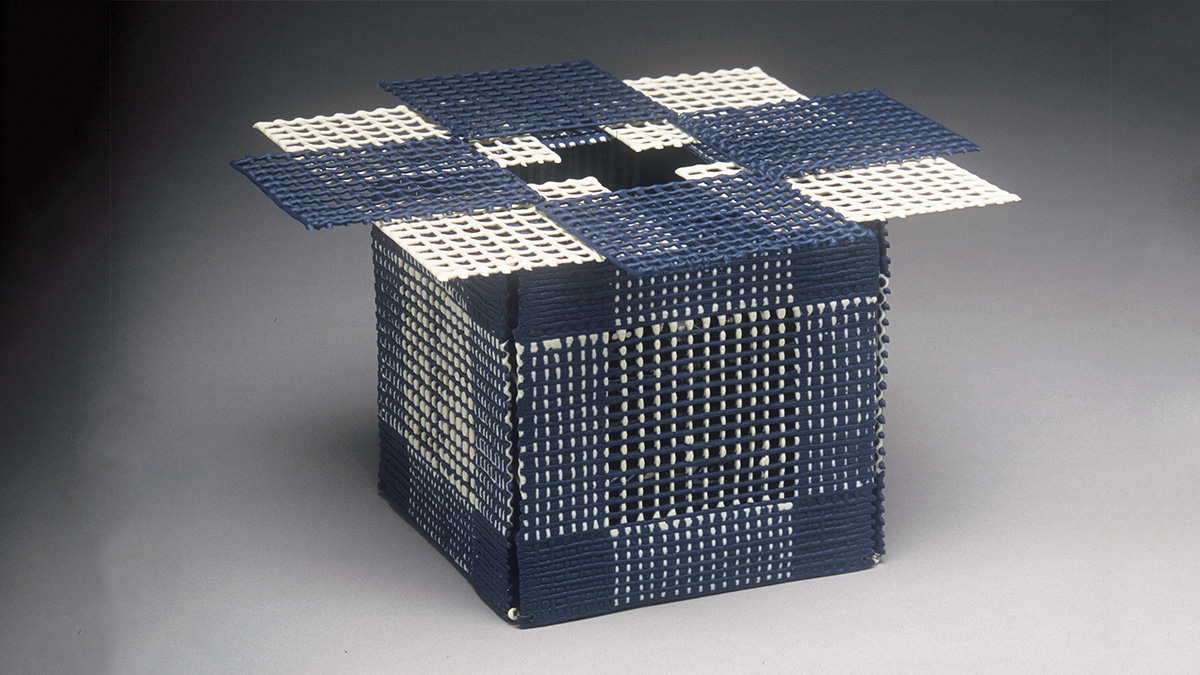

“The Cardiff Institute of Higher Learning was recommended very highly to me by Richard Slee, a British studio ceramist, while we were both at the Banff School of Fine Arts. He was a visiting artist and I was a resident. In the first few months, I made a series of master moulds for bowls, in the plaster studio, which was equipped with everything known to man. These moulds have produced many pieces over the years, and that was a huge learning curve for me at the time. The other 16 international students were all making ceramic sculpture, and so I was soon converted to making work with content, not necessarily functional. Our research papers had to reflect our work, and vice versa, and since my thesis was about women in craft, the symbols and icons used by women in textiles soon began to appear in my work, and have since become a part of my vocabulary. I traced the history of craft through textiles because there is a dearth of women in ceramic history. My work went in the direction of ceramic quilts, with blocks made of woven slip, and incorporating the research I was covering as time went by. Jeffrey Jones, my studio companion, has since written a well reviewed book on British Studio Pottery, and another colleague, Claire Curneen, has become highly recognized in the field. We had Michael Casson as our artist in residence, and Geoffrey Swindell was one of our teachers. They gave us the technical expertise, while Michael Hose and Peter Castle kept our noses to the grindstone, with Noel Upfold being our thesis tutor. My two years at Cardiff were remarkable in every way, the best years of my life.”

— Alexandra McCurdy, 2012

Martin Peters

“My pottery wheel was right beside Bill Marshall’s at the Leach Pottery. We both made Leach standard ware all day and talked and talked. Most of what I learned about British studio pottery in the sixties and seventies resulted from those discussions. John Reeve was managing the pottery at the time. On weekends John, his wife Donna Balma and occasionally Bernard Leach and I would visit Michael Cardew at his pottery in Wenford Bridge, Cornwall. The discussions around Michael’s kitchen table invariably turned to the state of studio pottery in England. At that time, the early 70’s, it was robust. It was in fact the product of everything Bernard Leach his wife Janet and Michael Cardew had been working and hoping for their entire lives: a public that was understood and very much appreciated handmade objects that formed part of their daily lives. As an apprentice at the Leach Pottery this daily exposure to these giants of studio pottery in England, their ideas and most importantly, the resulting form of the pots they made forever shaped my understanding of what is a good pot and accordingly, my own work. The Leach tradition, founded in English slipware but deeply influenced by the orient became the touch stone of the pots I produced upon my return to Canada in the mid-seventies. It remains today the seminal basis for everything I make in clay.”

— Martin Peters, 2012

John Reeve

“I went to see Leach in Seattle when he was visiting, I brought my best pots to show him. He told me what was wrong with the pot, why it didn’t work like it should. I listened to him and tears came into my eyes because I knew that what he was saying was what I shouldn’t do. But I had done exactly what I had intended. That was the moment when I realized that Bernard was not the Master anymore. For better or worse, I was a different person, a different potter, a different soul.”

— John Reeve, cited from Scott Watson, Naomi Sawada, and Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery., Thrown: British Columbia’s Apprentices of Bernard Leach and Their Contemporaries (Vancouver: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, University of British Columbia, 2009)

Juliana Rempel

“My initial decision to attend the Cardiff School of Art and Design was to bring my studies into close proximity with the extensive industrial history available within Britain and the rest of the United Kingdom. What I ended up receiving was a greater understanding of how this history has served contemporary ceramics both technically and conceptually. From mold making techniques to hand building, I was able to use both these applications in the creation of my own work but it was on a conceptual level, understanding the symbolic nature of these objects in our lives, which was of most significance.”

— Julian Rempel, 2012

Sam Uhlick

“I am not one of those people who made functional ware for my bread and butter, but wanted to make ‘true’ art. Functional pottery is just as valuable as art vessel.”

— Sam Uhlick, 2004