Best in Show with curator Natalie Hume

Before dogs became known as our furry, four-legged best friends, they held a variety of other roles in cultures throughout history. Prior to the invention of the compass, dogs were our guides, not only in this world, but also the next: in many cultures, dogs were thought to be guardians and guides to the underworld.

In 18th century Europe, the popularity of keeping dogs as pets rose in tandem with porcelain collecting. In fact, ceramics was one of the first mediums in which dogs appeared as the primary subject—previously, they would have appeared as secondary figures in hunting scenes or as companions following their owners, for example.

The current display in our lobby showcase, Best in Show, spotlights a diverse range of canine-centric ceramics dating from 300 BCE to the 21st century, and reveals how artists have used clay throughout history to convey the varied relationships between dogs and people. We asked curator Natalie Hume to share with us her five favourite dogs from the display, and which one she would ultimately crown “Best in Show.”

‘Howling-Dog’ Vessel, Colima or Jalisco, Late to Terminal Formative period (300 BCE 300 CE), Earthenware and brown slip, Gardiner Museum, Gift of George and Helen Gardiner, G83.1.38

In Colima cultures, howling dogs were an omen of death. Dogs were seen as both a guardian and a guide to the afterlife, which is why so many ceramic dog figures, like this one, were found in ancient burial tombs. Dogs were also linked with Xolotl, the god of fire and lightning, who was depicted with a monstrous dog head in paintings and mosaics. The connection between dogs and death can be mapped across history and geography. In Greco-Roman mythologies, the three-headed dog Cerberus guards the entrance to Hades, and in Jewish culture, dogs were thought to be able to see the angel of death.

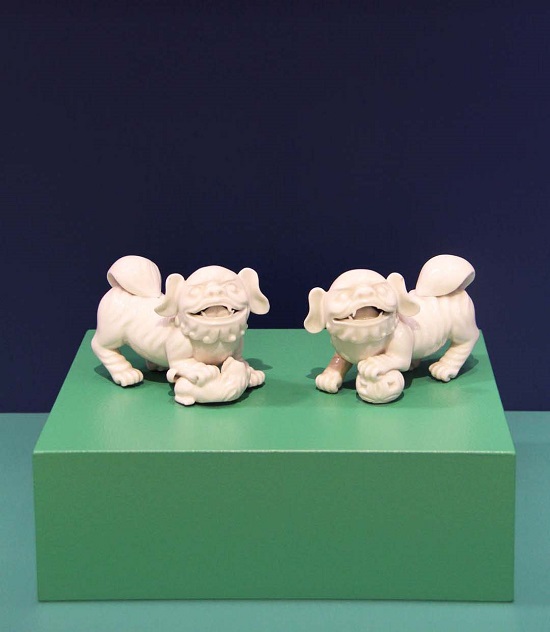

Pair of Fo Dogs (lion dogs), China, Dehua, 19th century, Porcelain, Gardiner Museum, The Anne Gross Collection, G18.1.7.12

These fo dog sculptures may have functioned as paper weights and were part of an essential set of items required for any scholar’s desk in Japan. Rooted in stories and myths from the Buddhist tradition, fo dogs developed from an amalgamation of a lion and a dog. They’re often seen guarding temples, shrines, and places of worship, and always appear in pairs for balance: the female dog symbolizes the yin, and the male dog symbolizes the yang.

Figure of a Puppy, Japan, Hizen, c. 1680-1690, Porcelain with overglaze enamels, Loan from the Macdonald Collection

Many people now acknowledge the health benefits of having a dog, but they once played a specific medical role in China: for muscle aches and pains, physicians would recommend holding a dog to the affected area, much like you would a hot compress, to relieve soreness. In China and Japan, dogs markings were described as flowered, which perhaps explains the flower-like markings on this figure.

Clock with Harlequin Playing Bagpipes and Pug Dog, Germany, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, c.1745-1752; Modelled by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Hard-paste porcelain with overglaze enamels, French orm

This clock features two separate but very popular Meissen figures—a harlequin and a pug dog—that were not intended to be displayed together. These pieces were imported by Parisian dealers of luxury goods known as “marchands merciers,” who would buy unpainted Meissen figures in mass and embellish them, creating new luxurious items to be sold in France. In this example, a minstrel is seen with his dog, an image that dates back to ancient Greece. A funny story: Empress Josephine, the first wife of Napoleon, had a possessive pet pug who loved to sleep in her bed and would get jealous of Napoleon, once biting a chunk out of his leg.

Best in show: Pair of Pug Dogs, Germany, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, c. 1740; Modelled by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Hard paste porcelain with overglaze enamels, Anonymous Loan

The pug dog has an interesting history. The breed originated in China and came to epitomize the voracious Western appetite for Eastern goods. Pugs, along with porcelain, were imported into Europe at the time of colonial expansion and the two became associated with one another. The story behind Meissen’s porcelain pugs is a fun and fascinating one. In 1739, Pope Clement XII forbad Catholics from joining the Free Masons, a quasi-religious fraternal organization. As a light-hearted response, the Order of the Pug was formed, a society which was quite revolutionary at the time for admitting women as well as men. New members were required to kiss a pug’s backside as part of the initiation ceremony, but porcelain pugs were often used instead.

Best in Show is on view in our lobby display case until March 17, 2019.